The Power Law of Practice & Diminishing Returns

The power law of learning/practice explains the non-linear relationship between the amount of time you spend working on a skill and the actual improvement you may see in a skill over this period. This is similar to the law of diminishing returns. These both show a negatively accelerating relationship whereas the time spent increases, your ability will increase by less and less. The important parts to focus on here in my opinion are the your ability/understanding increases greatly in the beginning and also that we don’t ever stop improving/learning, we just do so at a rate which has a lesser impact as we continue to improve.

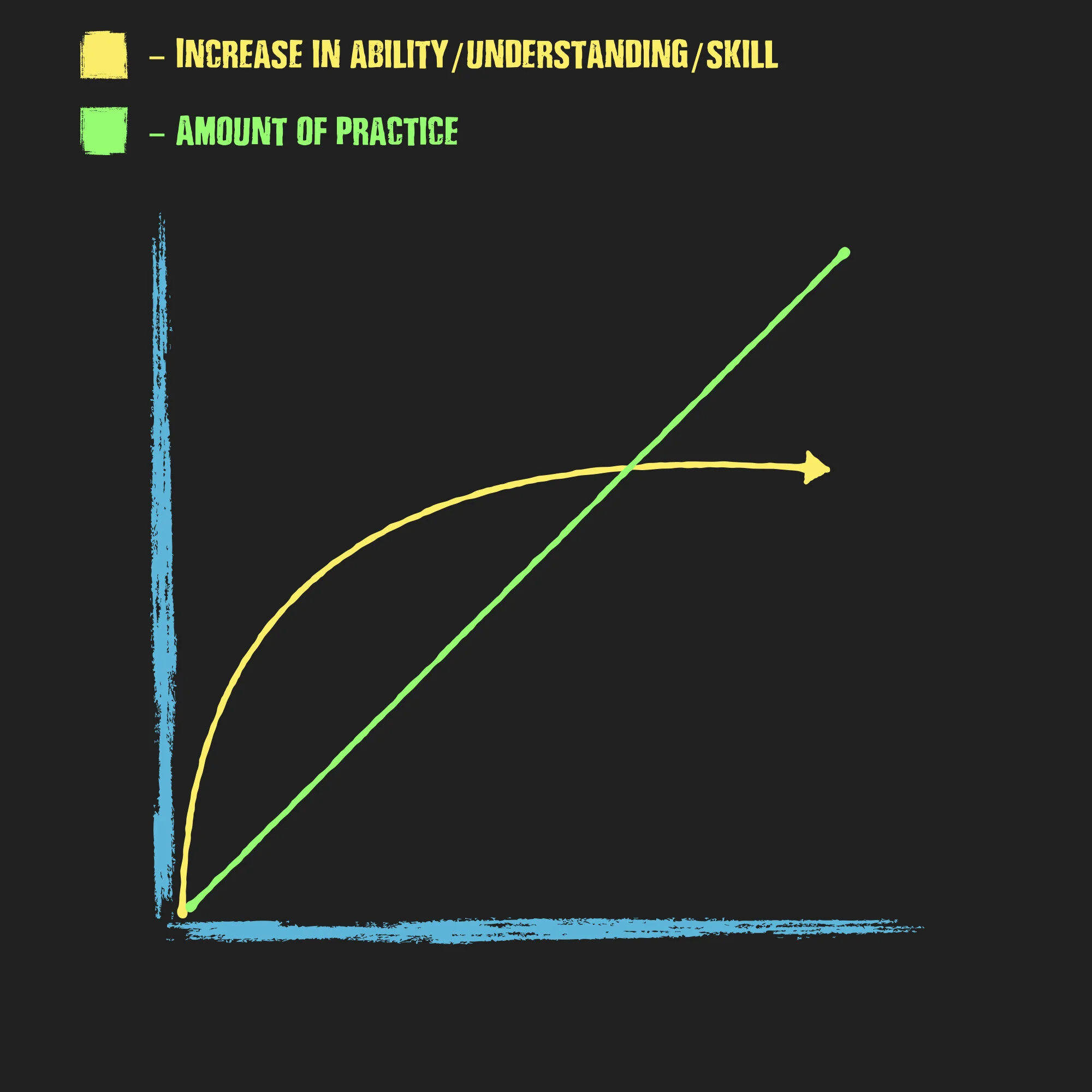

Essentially, as we first learn a skill or about a topic, there is lots of improvement to be made, and therefore, we improve much quicker. However, as you can imagine, as we continue to progress even multiple years into working on a skill, each unit of time we spend is going to have a smaller and smaller effect. For simplicities sake, if you know 1% about a topic, and you learn another 1%, you have doubled your knowledge. Whereas if you know 74% about a topic, and learn 1%, then you have made only a small increase. This is an example which doesn’t make technical sense but helps illustrate what I am talking about. This diagram should help illustrate what I am on about:

When you first started learning English, every word that you learned how to read or say was a much bigger proportion of the total of what you knew and had a greater impact on your ability to communicate, whereas now, where you have likely spent many thousands of hours communicating and learning how to do so, if you learn one word, it only improves your ability to communicate marginally. This goes across pretty much any example where you are learning something new.

This can also apply to physical improvement such as with strength training. Someone brand new for a number of reasons including neurological and muscular adaptations will increase their ability exponentially over the start of their lifting experience. However slowly this speed will reduce as to further gain adaptation, it will take much more work.

Also, you can think about how our body may respond to stimulus we place on it and the effect this might have on performance. In the same period of time someone might go from being able to squat 100kg’s to being able to squat 110kg’s while someone else might go from a max of 225 to 227.5. On the surface, the person who added 10kg might look like they have improved much more, and they have, but this won’t necessarily reflect the amount of training and the quality training the two individuals put in. Even if they put in the same effort, the person who started out lifting more, has already pushed their body to a much higher level and thus it will take relatively more effort to increase their ability the same amount.

Further, the impact on performance will be very different. It has been consistently shown that after an athlete surpasses 2x bodyweight on their squat, and further increases will have a negligible impact on their sprint time. This means that if someone increases their weight that they can squat from 1.2 to 1.3, their sprint time will benefit much greater that someone who improves from squatting 2.1 to 2.2 times their bodyweight. This means there will be greater transfer from squatting to sprinting earlier in our time lifting. This can show us where we may direct our time.

By understanding this concept, we can properly allocate our time learning and training to better reach our goals. Using the squatting example, if we want to increase our sprint times, in the beginning, while we are still newer to training, it might be worthwhile spending some time in the gym squatting to help improve the strength of those same muscle groups we use when sprinting. However, if we have already pushing this training method of squatting to the point where the investment in time yields us less improvement in performance, while we might not stop squatting completely, we may shift our focus to using other exercises which help our sprinting in other ways, or we may even just spend that time working on our sprinting.

Similarly, if you are studying for an exam, And 80% of the course you have spent a lot of time on already and have a good understanding of it, and the other 20% you still need to work on, you should spend more of that time learning the concepts you don’t completely understand. This is because the time you invest in studying will increase your understanding by more compared to if you just revised over the things you already knew.

As I have shown here, we can use this power law of learning and diminishing returns to select how we use our time and allocate it based on our goals and current ability.

The other part about this which I like, is that is can be applied in the micro also. Within training and practice, the more time you spend on a drill doesn’t necessarily mean you will improve by that much in the training session. Even if you haven’t reached your “full potential on that drill, there is only so much improvement which can occur during the singular training session.

For example, if you have one hour to learn how to shoot a basketball, you probably aren't going to improve the same amount throughout. Given that you have a decent coach with you, you might warm-up by shooting a few shots, your coach may then slow it down and break down what they think you need to focus on to improve, and then you might practice that for the rest of the session. After receiving instruction, if it's appropriate, then you will probably improve a bit right after, but then your ability won't keep increasing linearly because there’s only so much you can process in that short period of time.

Similarly, if you try and study all of the content for a full subject in 8 hours all at once, you are likely to understand those first concepts you learned at the start of the 8 hours pretty well, but then at the end, you may not understand nearly as much. Rather you want to split this up over a number of weeks. Let’s just say that the 8 hours to cram are all you really were going to need (it normally isn’t). If we split this up into 16 half-hour period over a couple of weeks, you are going to retain much more information.

So how do we apply this within our training sessions? There are a couple of considerations which you should apply when you plan training/study/practice.

The first is to try and spread out your training and take breaks. This is only possible to a certain amount. Most grassroots team sports only have an hour worth of training a week and most people don’t have 32 separate half-hour periods to study a week. However, where we can, we should split up training into more manageable periods.

The second which I think is important is to be aware of if you are getting anything out of continuing training or trying to understand a concept within a given time period. If you have been practicing a specific shot for 32 minutes, and there hasn’t been any improvement in the last 15 minutes, maybe it’s time to move on to a new drill. Decide a new skill to work on or change how you are working on this one, you have reached the point of diminishing returns and by continuing this drill, you are making inefficient use of your own time.

It is important to understand that this process is natural and occurs everywhere. However, if we understand it, then we can apply it to learn better, understand where to put our time, and to know when we want to continue practice/learning even if we are experiencing diminishing returns. Use it so that you can approach training, practice, and even your own learning better. Know when to move on and when to learn a new skill.

With this being said, however, also understand that sometimes continuing to learn past this point of diminishing returns is also where people start to excel. Without it, we wouldn’t have leaders in the industry. If you do enjoy learning about a topic or practicing a skill, embrace it. Continue to train and learn because once you find what you enjoy you probably want to keep going. I often enjoy most of the conversations regarding the nuance or minutia of a topic. While technically this is not “time-effective” and if I spent that hour learning about something new rather than discussing the specific biomechanics of the hip in a squat and the external and internal rotation in this motion, I enjoy it, and therefore, it is more than worth it for me.

Essentially, as I contradict myself at the end of this post, what I’m trying to say is that there is now set way to learn and improve to become the best version of yourself, however, we have concepts and guides and examples on how we can get there. I use the concept which I have spoken about to guide some of my decisions especially pertaining to how I use my time. It is a useful tool to apply throughout your life. However, at the same time, it can be good to embrace these “diminishing returns” if it is something that you actually enjoy.

I hope me sharing the use of this concept has helped you today. If it did, follow me in a number of places (links at the bottom of the page) and I will continue to share these things that interest me also.

Either way, thank you for reading!